[Webinar] State of the Audit: What auditors and banks need to know about the effects of COVID-19

- 4 minutes read

“Booms help fraudsters paper over cracks in their accounts, from fictitious investment returns to exaggerated sales. Slowdowns rip the covering off.” — The Economist, April 2020

We’ve seen this before. After the dotcom bust in 2000/2001 and the financial crisis in 2008, many fraudsters across the globe could no longer cover their tracks. Names such as Enron, Bernie Madoff, and Parmalat became the stuff of legend. And it’s happening again now.

The measures taken to slow the spread of COVID-19 are causing the biggest economic disruption since 2008, and auditors and financial institutions need to be prepared. To that end, Confirmation, part of Thomson Reuters, held an online event in May 2020 featuring Brian Fox, Confirmation’s founder, on fraud—and other significant changes—in a post-COVID-19 world.

If you missed the live event, you can watch it below.

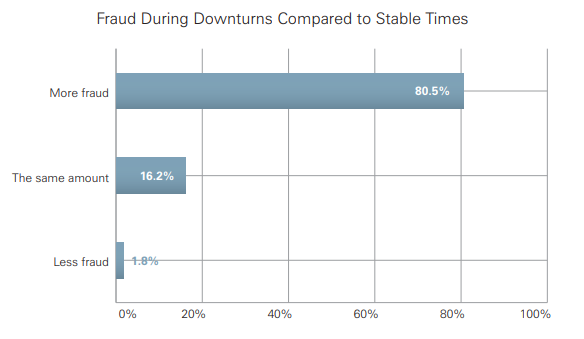

A key part of this live conversation is a look back to the financial crisis of 2008 and what we can learn from it. Brian mentions a 2009 report from the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners showing that fraud is uncovered 80.5% more often in economic downturns than in stable times.

“The message to Corporate America is simple: Desperate people do desperate things,” said ACFE President James D. Ratley, CFE, in 2009. The same economic pressures that created such a finding in 2009 exist now – employees taking pay cuts or losing their jobs.

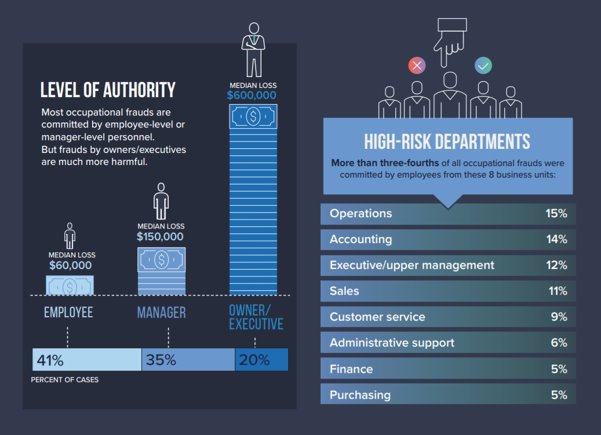

The ACFE’s new 2020 fraud report shows that the average loss per fraud case is now $1.5m, most being carried out internally. And while company owners and executives are responsible for only 20% of all frauds, these have a median loss of $600K, ten times that of lower-level employees. (See their two graphs below)

Big frauds of the past 20 years show the auditors of today exactly how fraudsters do what they do—providing big clues to activity that should raise a red flag. Take the Parmalat fraud, Europe’s largest fraud on record. It was this fraud by Parmalat senior management that helped put the idea of third-party confirmations in the pages of The New York Times.

Parmalat had inflated its revenue for a decade, becoming a $5bn company. By December 2003, it had borrowed billions of dollars, but when creditors asked for the debts to be serviced, Parmalat had no money to pay.

The scandal gave auditors a black eye. With hindsight, we can see why they should have been suspicious. The forged confirmation used a bank logo. The figures matched exactly. It was all too neat. These forgeries are all too easy to create, then and certainly now, which is why many firms have switched to online confirmations through the Confirmation platform.

Fast-forward to 2020, and alleged frauds are being exposed at an alarming rate. Luckin Coffee, where 35% of the revenue is feared fraudulent; NMC Health, where somehow the board didn’t know they had $3bn of extra debt on their books; and Total Education, which was charged with inflating revenue.

What do many recent frauds have in common? They were identified by short-sellers and other “happy accidents” rather than by auditors. Indeed, after the 2007/08 crash, it was short-sellers, not auditors, that were responsible for spotting some of the reverse Chinese merger frauds.

Auditors must step up and elevate their role in preventing and detecting financial crime.

Confirmation has helped auditors identify billions of dollars in fraud–we help the good guys catch the bad guys. How can that continue? Auditors need more training on finding fraud; they have to understand what motivates people and how they go about committing fraud. It has to be part of their DNA. They also need the right technology to be able to do it, which is where Confirmation comes in.

This State of the Audit conversation touches on all these points and more. Once you’ve watched it, please reach out to us if you’d like to know more about Confirmation or anything you heard in this recording. We’re here to help!